The semiconductor industry no longer faces the bulk of the supply chain challenges triggered by the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

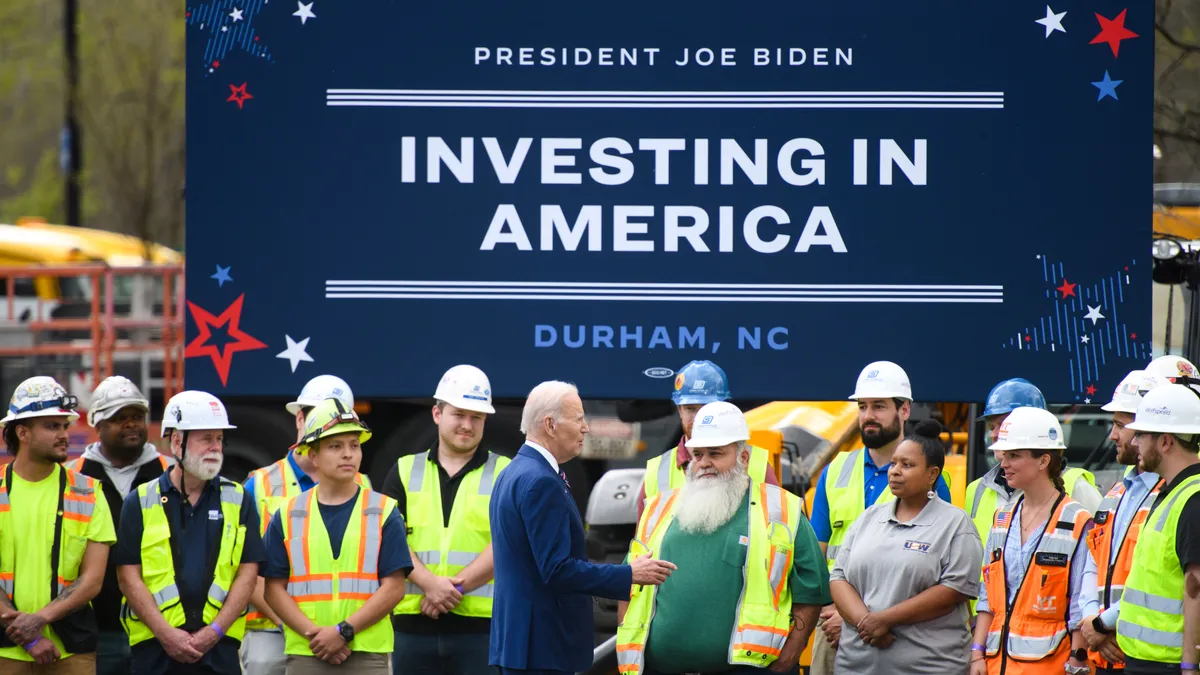

Instead, the U.S. chip industry is in major growth mode. Billions of dollars in funding is now available through the CHIPS and Science Act to boost domestic growth in the industry, with a total pot of $52.7 billion for semiconductor research, development, production and workforce development, including $39 billion in manufacturing incentives.

Emerging technologies are also enabling new applications for semiconductors across the market. Artificial intelligence-related applications have fueled demand for advanced semiconductors, while technology-enabled cars — as well as battery-powered electric vehicles — are now the top application driving semiconductor sales, according to a recent KPMG report.

The Department of Commerce has begun awarding some of the first grants under the CHIPS and Science Act. In January, it awarded semiconductor manufacturer Microchip Technology $162 million to increase its domestic production. Other chipmakers have also publicized their intent to apply for funds. Amkor announced plans in December to build a $2 billion advanced packaging and semiconductor test facility in Arizona and apply for federal funding to help pay for the project.

Still, time remains a major challenge facing the U.S. semiconductor industry, even amid the excitement spurred by increased government funding, explains John VerWey, an advisor in the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s global security, technology and policy group, who studies semiconductors.

"The actual construction time from the date of breaking ground to the first wafers being manufactured, it kind of nets out to around two years," he said. "But that does not take into account any of the pre-permitting [or] any of the permitting that happens before you break ground."

U.S. funding emerged amid a domestic chip shortage that hit the auto industry particularly hard, but factories can take several years to construct, which means it could be some time before that investment will translate into expanded manufacturing capacity, VerWey said.

And that financial support is primarily directed toward boosting U.S. technological advantage and reducing dependence on foreign producers like Taiwan for advanced semiconductors. This often doesn’t include a focus on the more simple chips that experienced a shortage in the auto industry during the pandemic.

At the same time, building new factories and starting from “scratch” is significantly more difficult than adding production at an existing plant, said Patrick Penfield, a supply chain management professor at Syracuse University. Because of this, U.S. manufacturers are behind competitors in producing the most advanced chips.

“When you're making huge monster investments like this, you're talking probably five or six years before you actually start to see some type of production,” Penfield said. “To manufacture these really highly advanced chips [is] extremely hard. You have to have experience and you have to have the workforce and the knowledge to be able to produce those types of chips.”

Notably, chip companies face several chokepoints throughout their supply chains, with sometimes only one or two companies producing a part they need. For example, only three companies in the world — South Korea-based Samsung and SK Hynix and U.S.-based Micron Technology — produce advanced semiconductor memory.

"When you're making a huge monster investment like this, you're talking probably five or six years before you actually start to see some type of production. To manufacture these really highly advanced chips [is] extremely hard."

Patrick Penfield

Supply chain management professor, Syracuse University

Another challenge facing chip manufacturers is a bevy of regulations. Chip factories use an intense amount of water and emit greenhouse gasses, making them subject to particular environmental rules, VerWey said. Companies building facilities in the U.S. must consider legislation like the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act, among others. Complying with these laws can be a new experience for chip companies, many of which are moving operations from overseas.

“Each country regulates emissions of those things differently,” VerWey said. “A Taiwanese firm may know what it means to have an adequate environmentally compliant HFC emission program in Taiwan, but it's different in the US.”

Finding and maintaining talent raises challenges too. One difficulty, VerWey noted, is finding workers who are familiar with the process of greenfield construction for fabrication plants, particularly because many haven’t been built in the U.S. for several decades. While chip factories are mostly automated, uniquely qualified workers are still needed to run the facilities.

“Over the next three years, talent will continue to be the most pressing issue facing chip manufacturers,” said Mark Gibson, national sector leader for global and U.S. technology, media and telecommunications at KPMG. ”The demand for technical talent is only expected to increase — and chip manufacturers are placing a greater strategic focus on talent development and retention ahead of supply chain resiliency.”

Some construction labor problems might abate, VerWey noted, as firms get more accustomed to building fabs. In terms of the workers who will one day operate these facilities, companies face two choices: attracting international talent or training and educating workers based in the U.S., he said.

The issue is one that Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company is dealing with as it builds two fabs in Arizona. The company has pushed back the opening dates of both facilities, including a delay on the first fab because of a lack of specialized labor in the U.S. TSMC had planned to bring in foreign labor to fill these roles, a move that received swift backlash from local unions.

The company reached a deal with the Arizona Building and Construction Trades Council earlier this month, which included a stipulation to focus on hiring workers locally. The agreement could be a bellwether for how recruiting will be handled at other upcoming chip plants.

"The goal is, eventually, hopefully to get to those high-end chips,” said Penfield. “But I think probably the middle of the range is what we'll see from a chip manufacturing standpoint as far as the complexity and the capability of those chips."