Editor’s note: This story is part of an ongoing series diving into the opportunities and challenges facing the manufacturing industry in 2023. Read the rest of the series here.

When the National Association of Manufacturers surveyed industry players about their biggest business challenges in August 2022, over three-quarters of respondents listed attracting and retaining a quality workforce among their top issues.

Months later, little has changed. “Manufacturing companies still are struggling to find workers,” NAM Chief Economist Chad Moutray said. “Everywhere I go, they tell me that is still one of the top issues, and job openings continue to be really elevated.”

Nearly 780,000 jobs were unfilled in the industry as of November 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But amid those thousands of open roles, some are proving particularly hard to fill. As technical skill requirements and academic interests continue to change, companies are struggling to find production workers, engineers and middle skill workers, a problem that experts say is unlikely to subside in the year ahead.

Production workers

Much of today’s staffing challenge is centered on the shop floor.

“The position I hear the most is entry level workers” said Moutray. “The average pay for production workers in manufacturing is $25 an hour, and yet, there is a lot of competition for that talent.”

The competition has intensified as companies hike wages to vie for workers in an increasingly tight job market. In particular, manufacturers are finding themselves at odds with sectors that attract similar talent, such as warehousing and retail.

“You’ve got everybody from the Amazons, the Walmarts, the Targets, and the FedExs … and so forth, paying considerably more for entry-level blue collar talent,” said Erik Olson, a senior client partner with Korn Ferry, who specializes in advising industrial manufacturing companies. As a result, manufacturing has fallen further behind when it comes to base compensation ranges.

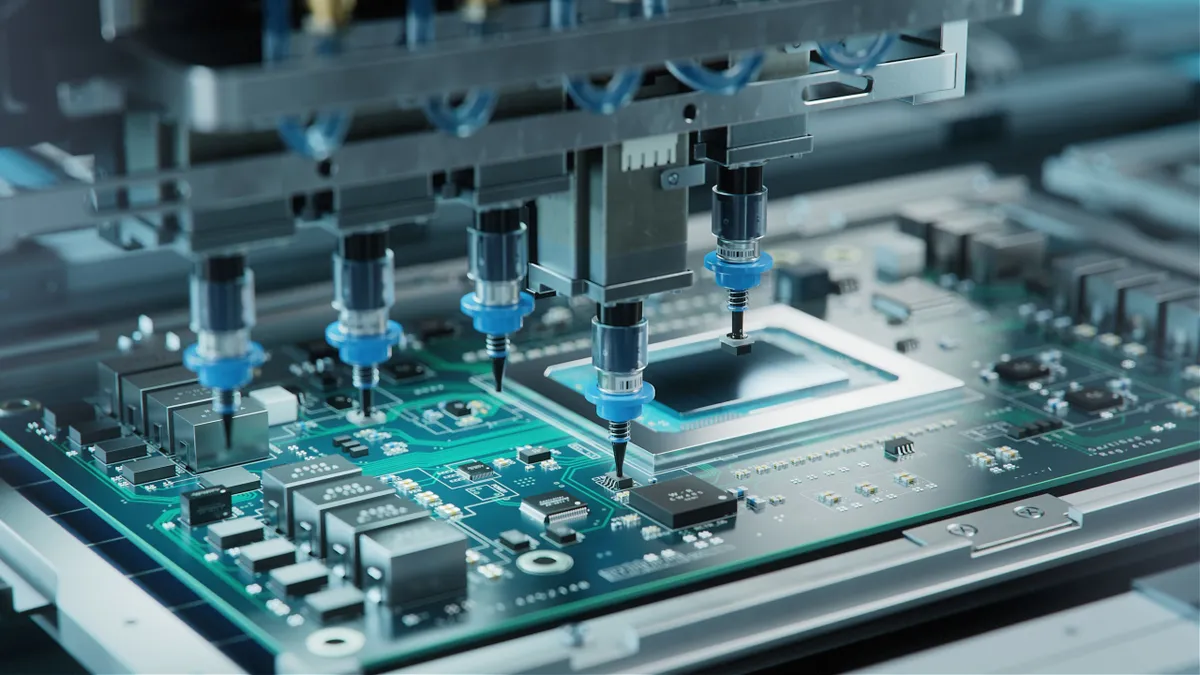

The industry’s digital transformation is also creating a mismatch between available workers and the skills needed to fill open jobs. Moutray explained that companies are constantly looking for workers that can leverage new technologies, which “takes a lot of folks off the table.”

“There’s no such thing as a low skilled job in manufacturing anymore,” Moutray said. “To really thrive, we’re going to need continuous learning and upskilling.”

Engineers

A scramble for engineers has also been brewing for some time, said Mary Ann Pacelli, former program manager for workforce development at the National Institute for Science and Technology’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership. She retired from the agency last month, most recently serving as division chief of National Platforms for the public-private partnership.

Fewer young people are pursuing careers in engineering as college populations level off, Pacelli said. As more baby boomers retire, she expects there won’t be enough students in engineering programs to fill the roles that open up in the next five years.

Doreen Poehlitz, human resource director for Bosch USA’s Charleston, South Carolina plant, said this trend is not new.

When she moved into HR more than a decade ago, Poehlitz recalled looking at statistics that revealed more international students than residents were graduating from engineering programs at U.S. universities. “Even back then, it shows the U.S. was falling further behind, especially on the engineering and technical side,” she said.

International students have played a critical role in filling demand for science and engineering talent in the U.S., according to a recent analysis by the National Foundation for American Policy.

Full-time international graduate students by field in 2019

Between 2014 and 2018, over half the growth in engineering graduate programs was driven by international students, who made up nearly 57% of the student engineering population in 2016, the American Society for Engineering Education found. At the same time, domestic enrollment in these programs slowly decreased.

However, international applications to engineering schools fell across the board in 2021, with the society citing the Trump administration’s 2020 policy change to student visas and COVID-19 travel restrictions as key factors.

Compounding the issue, Poehlitz noted, is competition between industries for a dwindling number of engineers in an increasingly digital environment.

“We have a higher amount of need now than ever, and a decreasing line on the opposite side of people becoming available,” she said.

Middle skill workers

After decades of pushing college education, the U.S. is experiencing a shortage of tradespeople.

The scope of these positions is vast, with experts calling out everything from electrical, mechanical and automation technicians, to CNC machinists, welders and maintenance mechanics.

The labor gap among these roles is exacerbated by a rising need for technical specialists who can work with automation.

“There’s no such thing as a low skilled job in manufacturing anymore. To really thrive, we’re going to need continuous learning and upskilling.”

Chad Moutray

Chief Economist, National Association of Manufacturers

Olson said that more than 70% of the clients his organization works with have increased automation over 50% in the past three years, upping the need for people in operational technology positions at the plant level.

“We’re producing fewer and fewer folks that come into the workforce in the areas that we’re talking about,” Olson said, noting a continued de-emphasis on technical and trade skills among the country’s youth has played a role.

As of 2012, federal figures on technical education showed that only 8% of undergraduates enrolled in certificate programs. In November, the Department of Education launched an initiative aimed at expanding access to skills-based learning and training programs in industries like advanced manufacturing, to ensure the “next generation” builds skills needed to fill in-demand jobs.

Such efforts are a reversal from the 1980s and 1990s, when a larger national push for students to attend four-year universities meant fewer people attended trade schools, said Patrick O’Rahilly, founder of manufacturing recruitment platform Factory Fix.

“That’s your skilled workforce a decade later, so without that, you get a real shortage, and that’s what we’re paying the bill for now,” he said.