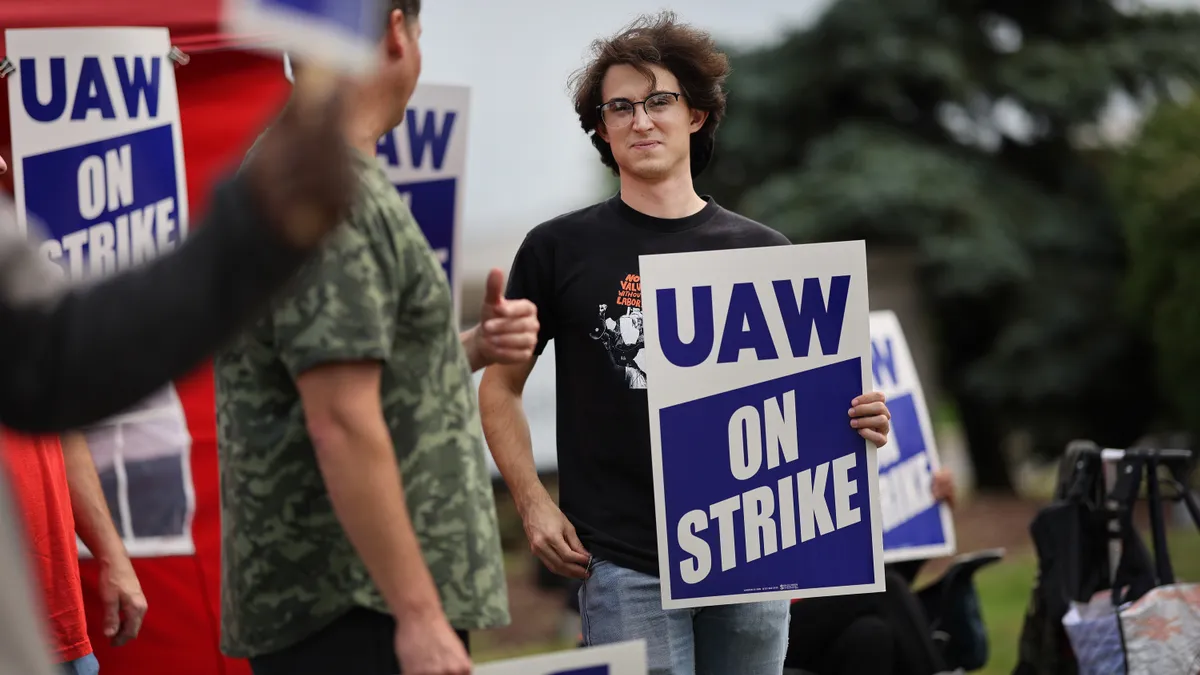

The transition to electric vehicles looms large over the United Auto Workers strike against Ford Motor Company, General Motors and Stellantis, which has spread to 41 plants so far.

“The sad reality is [the auto companies] are leaving our workers behind in this transition to EV,” UAW President Shawn Fain said last week.

The UAW is concerned that a transition to EVs carried out solely on the companies’ terms could lead to job losses for tens of thousands of members. What they want is for wages at battery plants to match that of unionized assembly plants, as well as protections for workers affected by the transition.

“Technically, the EV transition is not officially on the bargaining table,” said Tod Rutherford, a professor in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. Not like, for example, higher wages and retirement benefits, which are mandatory subjects of bargaining. “But unofficially, there’s clear subtext,” regarding the EV transition, Rutherford said.

Most directly relevant to the transition, the union is negotiating for the right to strike over plant closures and better compensation for laid-off workers. Earlier this year, Stellantis idled a plant in Belvidere, Illinois, and moved production to Mexico, indefinitely laying off at least 1,200 workers. Stellantis blamed the closure on the cost of the EV transition.

According to Rutherford, winning the right to strike over plant closures would allow workers to actually influence company strategy. He said the UAW would be able to pressure companies to offer better terms to laid-off workers, which could include better severance packages or job training.

In the past week, Ford conceded the right to strike over plant closures, increasing the likelihood the demand would be accepted by the other auto companies, especially GM. Ford agreed that laid-off workers would receive pay and health benefits for two years. Because of the progress the UAW has made with Ford in negotiations, a single Ford plant is on strike — the other 40 are split between GM and Stellantis.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government is trying to find a delicate balance between the move toward electrification and workers rights, with President Joe Biden emphasizing his commitment to both the energy transition and unions like the UAW. The Inflation Reduction Act created substantial incentives to invest in domestic battery plants, many of which are at least partly owned by automakers.

On the other hand, Biden became the first sitting U.S. president to join striking workers on a picket line, appearing at a Michigan GM plant on Tuesday. While the Biden administration references good-paying union jobs in the EV transition, government subsidies to automakers have typically come without job quality stipulations. Largely because of this, the UAW has so far withheld an endorsement of Biden (or anyone else) for president in 2024, Fain said earlier this year.

In addition, because of the structure of automakers’ battery plants, workers would not necessarily receive wages and benefits comparable to those of UAW members who build cars with internal combustion engines. Battery plants — the recipients of the government subsidies — are set up as joint ventures with other companies, rather than being wholly owned by the automakers. This means that these workers, even if unionized, may not be covered by the master agreements between the UAW and the Big Three. The UAW hopes to change this and include unionized battery plant workers in the Big Three contracts. Workers at Ultium, the Lordstown, Ohio, battery plant owned by a joint venture between GM and LG, recently unionized with the UAW and won higher wages, with hourly pay now between $20 and $24. This is still less than the approximately $32 per hour top wage of a unionized assembly worker.

Joint ventures are not necessarily a way to avoid folding these workers into the UAW. “The principal motivations in most instances are spreading the huge, fixed cost of building a battery plant and sharing the cost of technological development,” Stephen Silvia, a professor of international economics at American University and author of the book “The UAW’s Southern Gamble,” wrote in an email.

The technology needed to build batteries is expensive, and the automakers don’t have the research and development resources they’d need to build and operate these plants on their own, Silvia said. That’s why they’ve brought in technology companies like LG.

At the same time, “the companies would like to set the precedent of lower compensation at battery plants, if possible,” Silvia said, adding that the Big Three would prefer to pay wage rates similar to those paid at parts production facilities, which are less than the pay rates at unionized assembly plants.

Because the battery factories are not wholly owned by the automakers, this strike cannot legally be about the battery plants. According to labor law, unions are prohibited from targeting other employers in “sympathy strikes.” Administratively, joint ventures are different employers whose plants are not, at least currently, included in the master agreements.

But the UAW can still push for concessions on EVs, said Lee Adler, a labor, criminal law and civil rights practitioner and a professor at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. Adler said that as long as a mandatory, economic bargaining subject, such as wages and worker safety, remains on the table, actions over nonmandatory subjects are fair game.

The UAW could, for example, “leave pensions on the table, but really have their eye on the transformative [EV-related issues],” Adler said, explaining that that might be the best way for the UAW to get around not being able to officially bargain over the transition. Such issues are “not traditionally economic,” Adler said, “but they’re the union’s whole future.”

Considering the billions of dollars of subsidies automakers have received, it’s possible federal officials could help persuade companies to cut a deal with the UAW. Biden originally planned to bring in Acting Labor Secretary Julie Su and White House adviser Gene Sperling to help the union and the Big Three reach a settlement, but Fain said they weren’t needed in Detroit, emphasizing that the strike was the rank-and-file union members’ strike.

But Rutherford said the government “could probably push [automakers] more than they have” to create better jobs in EV plants by requiring companies that want to take advantage of tax credits, offer union-level wages, or practice union neutrality, which means refraining from interfering with organizing efforts.

Rutherford said the strike’s main priorities are still ending tiers and reversing the erosion of wages, but the chance of an EV transition that is unfavorable to autoworkers is impossible to ignore.

“The union knows that there’s a potential for job loss and also deunionization if they don’t do something about it,” he said.