The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency launched an extensive deregulation effort March 12, involving 31 actions meant to alleviate federal government oversight of climate-related rules.

The actions affect various industries, including manufacturing, and are part of EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin’s “Powering the Great American Comeback” initiative that aims to create more jobs and grow the U.S. economy.

Manufacturing trade groups such as the National Association of Manufacturers and the American Chemistry Council lauded the efforts, as they have previously urged Congress to curtail oversight, arguing it prevents innovation.

However, many of these deregulations won’t happen overnight, according to experts. The rules finalized under President Joe Biden will stay put as the EPA prepares to launch a comment period for each of the 31 reconsidered statutes, which could take months or even years.

The process could also be stalled by possible job cuts at the EPA, as well as potential legal battles from citizens and states that challenge the deregulations.

How long it will actually take for the changes to take effect is anyone’s guess, said Robert Helminiak, VP of legal and government relations at the Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates.

“Time is always a challenge,” Helminiak said. “If you have to go through an actual regulatory process, you're talking about years; nothing is instant with the federal government.”

A long regulatory process

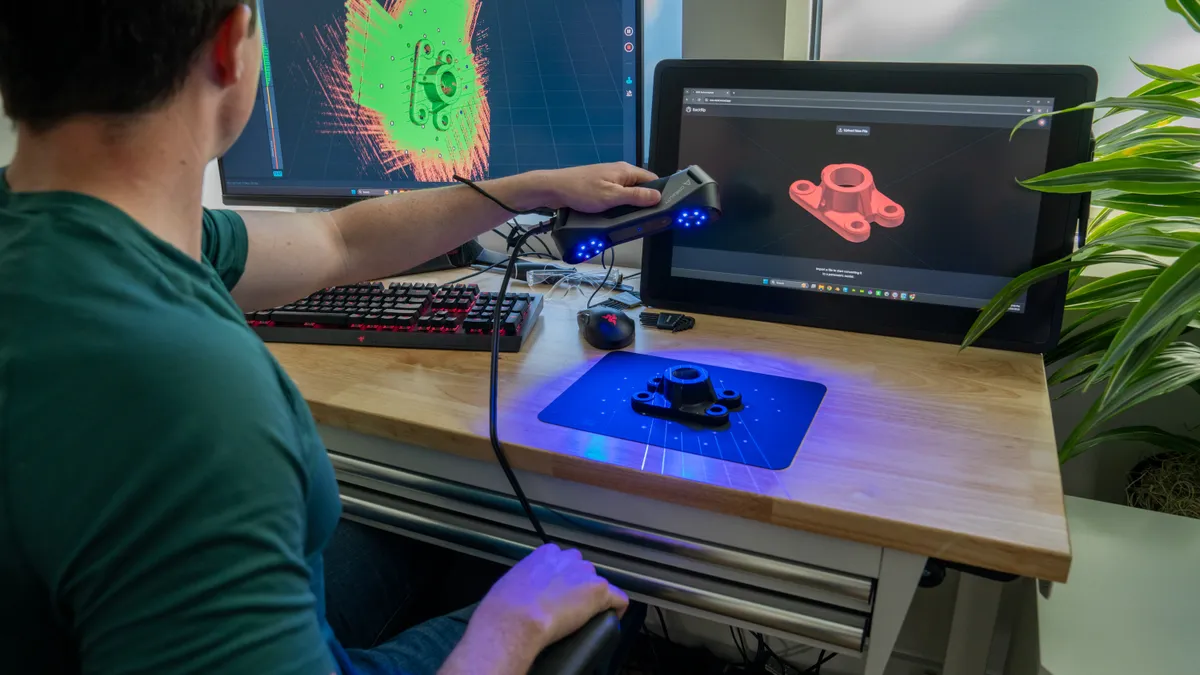

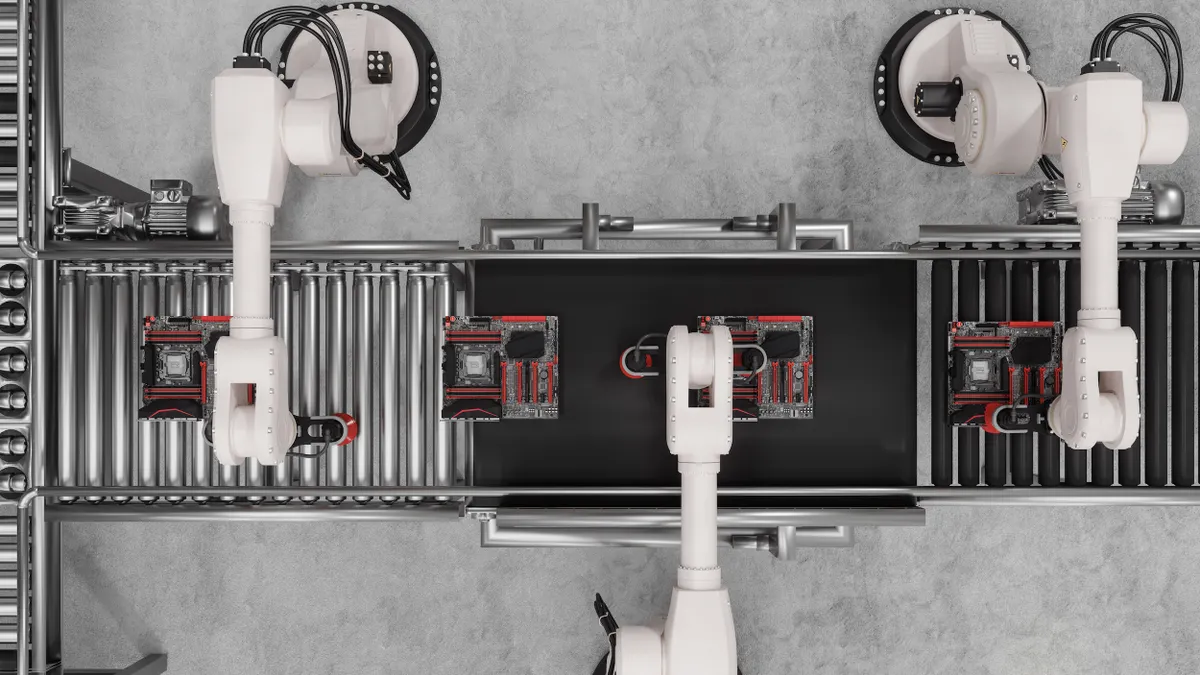

The overarching focus of these actions is to encourage reshoring and bring manufacturing back to the U.S., Helminiak said.

“It’s really to secure the supply chain, especially when we’re looking at things like in the pharmaceutical space or the defense space,” he said. “It’s to make it better and easier to manufacture in the United States. And of course, obviously, we want to do that in the safest fashion possible.”

The EPA will have to go through a rigorous process under the Administrative Procedure Act to roll back these regulations, said Robert Glicksman, an environmental law professor at George Washington University. The process involves proposing a rule, soliciting and considering public comments, responding to those comments and then issuing a final rule, which can take up to two years to accomplish, he added.

“Once we can dive deeper into these actions that the administrators outlined, we'll have to see what the strategy is and how they're really going to implement, if they're looking for input on that implementation, what we can do to sort of help with that implementation,” Helminiak said.

If Congress mandates the rule’s issuance, Glicksman said he expects the Trump administration to weaken the regulations instead of just repealing them.

Many of the regulations the EPA implemented were congressionally mandated, such as the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) under the Clean Air Act.

For NESHAP, the Trump administration is considering a two-year presidential exemption under the Clean Air Act, which would allow facilities to be exempt from the regulation while the agency reviews it, according to a March 12 EPA press release.

However, using this exemption will require a demonstration to prove pollution control technologies used to reduce toxic emissions from facilities are not available and that the move is in the interest of national security, said Nicole Waxman, an attorney at environmental law firm Beveridge & Diamond.

“We can foresee that the administration might ask or might try and collect some information relating to those two factors,” she said.

An uncertain geopolitical climate

One thing the EPA and manufacturing trade groups have in common is a reliance on scientists to research and collect data used to back regulations and industry changes.

However, the flurry of job cuts across many federal agencies could stall some of the revamps the Trump administration is trying to implement, and the EPA is no exception. Scientists at the agency could fall prey to the layoffs.

For example, documents reviewed by the House Science Committee Democratic staff unveiled plans to cut 1,540 positions at the agency’s Office of Research and Development, the New York Times reported.

If the job cuts happen, it could make the reconsideration process longer if there is less staff to address comments and review scientific research submissions, Waxman said. Still, she added, it’s hard to say at this point how long the process will take.

“EPA has to show that they’ve done their homework, too,” Waxman said. “They at least need to show that, in addition to reviewing data that they have themselves, they are reviewing all of the data that will be submitted in these upcoming comment periods.”

Glicksman said there's also a chance the rollbacks won't survive possible legal battles if the curtailment or cancelation of existing regulations is challenged.

“[If] the Trump administration wants to repeal or weaken that regulation, it's got to justify why it’s changing the rules of the game,” Glicksman said. “Unless it’s got strong scientific evidence that counteracts or contradicts the science behind the existing regulation, there’s a good chance a court could conclude that it was arbitrary of an agency like EPA to ignore existing science and nevertheless repeal or weaken regulation.”

What manufacturers can do as they wait

Until these regulations are officially modified or dismantled, manufacturers must still follow the current laws.

But in the meantime, manufacturers should keep an eye out on the regulations and gather all the technical support data to submit when the commenting periods for the reconsidered rules open, Waxman said. Companies can also watch for lawsuits pertaining to the actions and if there are opportunities to intervene.

“I think keeping an eye on those legal challenges and opportunities to intervene in those legal challenges is going to be really key over the next several years, because you certainly want to be able to tell the court you know how this impacts your company and your company's operations,” Waxman said.