All eyes have been on Boeing since a door plug blew out midair on an Alaska Airlines 737-9 Max in January.

Since then, the Federal Aviation Administration has significantly ramped up its oversight of Boeing’s manufacturing and has even put a halt to the company’s production expansion plans until its quality control issues are addressed.

More scrutiny and oversight may soon follow with two back-to-back Senate hearings on Wednesday.

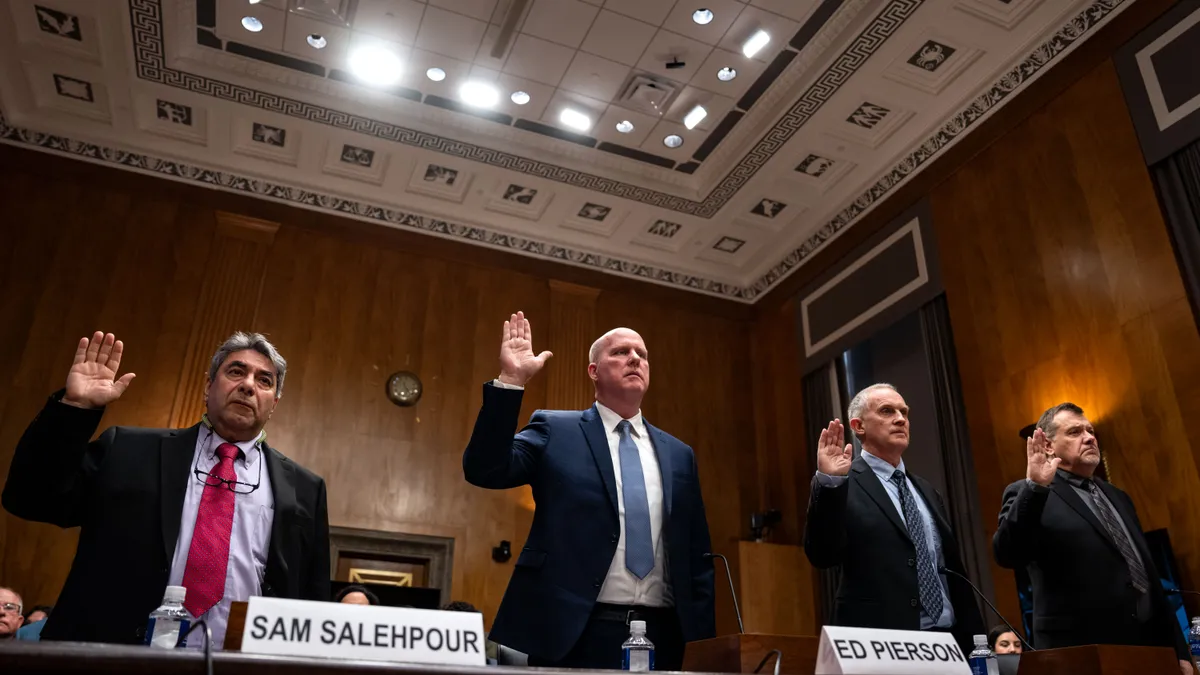

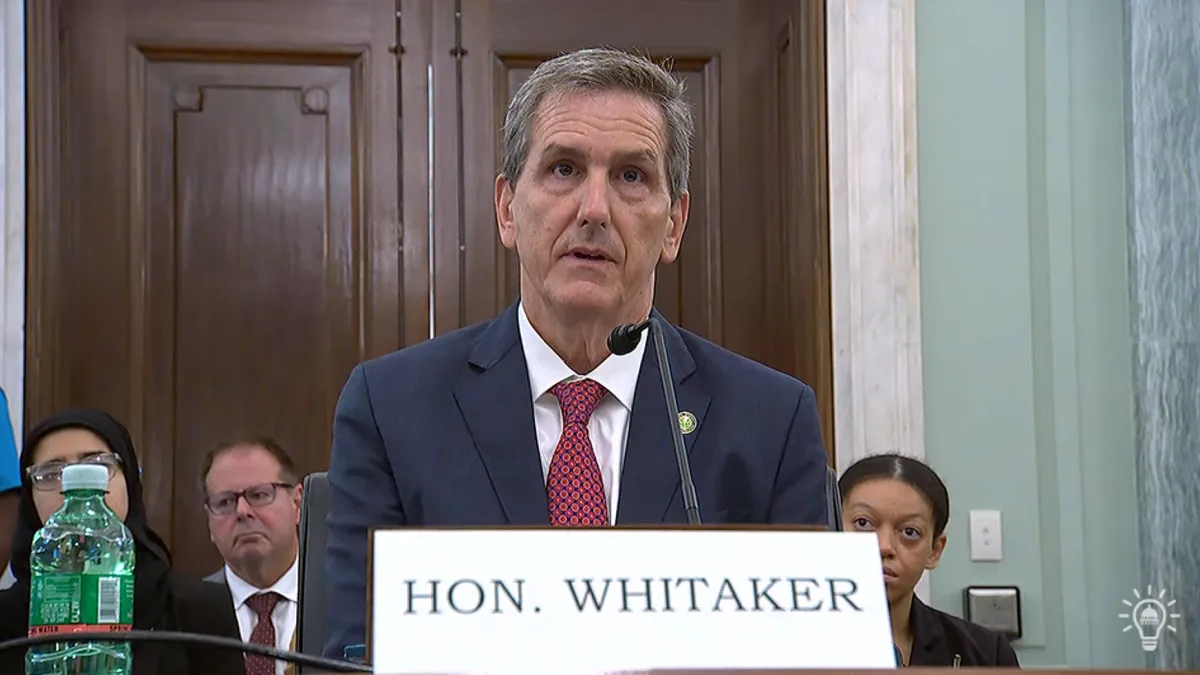

An FAA expert panel will testify before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation regarding an independent review looking at Boeing’s safety processes and culture, which was released in February.

The second hearing will have a Boeing whistleblower testify before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs’ investigation subcommittee.

The aircraft maker plans to spend between $4 billion to $4.5 billion this quarter to fix its production line as well as slow its 737 Max units assembly line, CFO Brian West said at a Bank of America conference in London last month.

“There's changes that need to happen, there's no doubt about it,” West told analysts at the conference. “But we're going to do so diligently and expeditiously. But we won't rush or go too fast. In fact, we're deliberately going to slow [production] to get this right.”

Getting to the root of the problem

To get to the the base of its problems, Boeing needs to start with stabilizing its manufacturing processes, said Bill Remy, CEO of supply chain firm TBM Consulting.

"What we would tell clients is, get it stable, get it to where [you can] follow your standard work in your standard process so we can see what that really is, and then we can work from there.”

Remy added that once production is maintained, the company can investigate the root causes and issues to assess next steps.

Boeing highlighted travel work — work completed out of normal production sequence — as a culprit behind some of its quality problems.

“Anytime work gets done out of sequence means you're not following standard work, which means now verifying and validating that it was all done correctly is harder and the risk of mistakes goes up,” Remy said.

Boeing no longer allows traveled work between fuselage supplier Spirit AeroSystems’ Wichita, Kansas, plant and the aircraft maker's facility in Renton, Washington, effective March 1, West said at the conference.

“So now we will only accept a fully conforming fuselage from Spirit [Aerosystems], which means in the near term, there might be variability of supply, but long term, the predictability that we're going to get is dramatically better,” West said.

Shutting down shadow factories

In addition to eliminating traveled work, Boeing needs to start moving experienced workers from its 787 and 737 shadow factories to the main production lines, said Richard Pettibone, senior manager of information services and government and an industry and aerospace analyst for Forecast International.

Shadow factories are the end of the production line, where workers address issues such as improper drilling component misalignments

“You have to establish a culture and a trust in everyone that says if I see a problem, I'm gonna say something and I'm gonna flag it.”

Bill Remy

CEO of TBM Consulting

Shadow factories don’t have the tooling or components needed at the end of the main production line, Pettibone said. Workers will be required to retrieve the tools or components necessary to fix the aircraft’s issues wherever the plane is stored at a separate facility.

The company plans to shut down its two shadow factories later this year, West said. Boeing will also move its most skilled labor away from rework and into production.

“We are intent on shutting them down as we exit this year and liquidating that inventory, delivering those airplanes to our customers," West said at the March conference. "And the productivity benefit is enormous because you're going to take some of our most highly skilled labor and point it away from rework and point it towards first-run production."

‘Safety and quality go hand in hand’

Boeing is also intent on addressing flaws in its management and safety culture, after a February independent expert review panel report found the system flawed.

“The linkage between safety and quality go hand in hand,” Remy said. “When we look at [the] performance of manufacturing companies, if they have a lot of safety issues… they probably have some quality issues as well.”

If a manufacturing company’s incident rates are high, it shows the work culture's willingness to follow procedures and standard work as well as how the organization is run, Remy said.

“You have to establish a culture and a trust in everyone that says if I see a problem, I'm gonna say something and I'm gonna flag it," Remy said. "I'm not gonna just let it go.”